In Gordon Dahlquist’s new novel The Different Girl, Veronika, Caroline, Isobel and Eleanor are four young girls who live on a small island with their two adult caretakers Irene and Robbert. The girls are completely identical aside from the color of their hair: one is blond, one brunette, one red, and one black. They don’t know exactly why they’re on the island; all they’ve been told is that their parents died in a plane crash so Irene and Robbert are raising them there. Each day passes more or less like the last: the girls wake up, do a number of learning exercises under the guidance of the adults, help with meal preparation, and go to bed.

Everything changes when a different girl arrives on the island under mysterious circumstances. She looks different, she speaks differently, she knows and says things the other girls don’t understand. Gradually everything begins to change as the four girls learn more about their true nature and their origins.

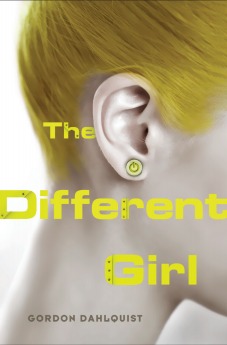

The best way for you to decide whether you’ll enjoy The Different Girl is by reading the long excerpt recently posted on this site and then decide if you’re up for reading another two hundred or so pages in the same style. The excerpt, which comprises the entire first chapter, will give you a good idea of the tone and pace of the novel. More importantly, at the very end of the excerpt you’ll get a solid hint of what’s really going on. Another hint can actually be found right on the cover. (I love that cover design, by the way, even though the placement of the button is somewhat inaccurate.)

The main problem with The Different Girl is that the entire novel is told from the same, very limited perspective as that opening chapter. While this consistency is in itself admirable, it results in a narrative voice that’s incredibly, almost bizarrely monotone. The girls have no frame of reference because they are literally learning how to think on their island. They’re being familiarized with basic cognitive processes:

After breakfast we would cross the courtyard to the classroom, but on the way we would take what Irene called a “ten-minute walk.” Robbert’s building was actually right next door, but we always started our trip to school the same way. This meant we could go anywhere we wanted, pick up anything, think of anything, only we had to be at the classroom in ten minutes, and then we had to talk about what we’d done or where we’d been. Sometimes Irene walked with us, which made it strange when we were back in the classroom, because we’d have to describe what we’d done, even though she’d been with us the entire time. But we learned she was listening to how we said things, not what, and to what we didn’t talk about as much as what we did. Which was how we realized that a difference between could and did was a thing all by itself, separate from either one alone, and that we were being taught about things that were invisible.

This frequently leads the girls to insights about consciousness and reasoning that they simply don’t have the vocabulary to express:

I was outside of everything they said, like I listened to their stories through a window. I could imagine everything they said—I understood the words, but the understanding happened in me by myself, not in me with them.

Again, it’s admirable that Gordon Dahlquist chose to tell this story entirely from the point of view of one of the girls. It’s a fascinating thought experiment, and it creates intriguing puzzles and mysteries for the reader to solve. As the story progresses, you’ll be able to figure out more about what happened in the past and in the wider world, about the girls, about their two caretakers, and about how they all ended up on the island. Most of this is set in motion with the arrival of the mysterious new girl. As a plot and a backstory it’s actually not all that original, so when all’s said and done the main attraction of the novel is unfortunately the way it’s narrated.

The Different Girl is basically over two hundred pages full of introspection and basic reasoning by a character who barely has a personality. She wonders in detailed but very simplistic language about why everything happens, why she is becoming different, why she stayed somewhere for 90 minutes when she was only told to stay for 45, what this implies, and so on and so forth. She has no frame of reference for anything except for what she’s seen on the tiny island that she’s been on all her life. All of it reads like a child’s attempt to narrate a psychological novel. The best word I can think of to describe this novel’s narrative voice is “droning.” As a concept it’s somewhat interesting, but in practice, much as it pains me to say it, the end result isn’t.

As an example: there are little or no metaphors or similes, because the girls don’t understand them and haven’t been trained to use them. There’s actually a point late in the novel where the narrator is confused because one of the adults sometimes describes things differently “from what they actually were,” saying things like it’s “hot enough to fry an egg,” which is hard to comprehend for the girls because there actually aren’t any eggs being fried anywhere outside. The entire novel is told this way: no imagination, no humor, no emotion. Of course that’s more or less the point of the story and, again, the consistency Dahlquist brings to The Different Girl is commendable, but the end result is simply too dry and boring.

In the novel’s Acknowledgments, the author mentions that The Different Girl started out as the libretto for an opera. I could actually see this story working well in that format. A musical, visual version of the events narrated by Veronika would probably have much more impact and could be enchanting if executed well. Unfortunately, as a novel, it’s less than successful.

The Different Girl is published by Penguin. It is available February 21.

Stefan Raets reads and reviews science fiction and fantasy whenever he isn’t distracted by less important things like eating and sleeping. You can find him on Twitter, and his website is Far Beyond Reality.